A few years ago I was called into a project which regarded Sinti, Italian gypsies, as they call themselves.

The socio-sanitary district of the mayor office of a big Italian town had arbitrarily decided to assign some popular homes to the gypsies in order to consequently dismantle their camp at the periphery of the city. The officers had not done any analysis of their needs nor had met other than superficially with their comity. They expected gratitude and an enthusiastic response: who doesn’t desire a home? When the Sinti population had not responded as the social officers expected, a study group was organized, calling for a consultancy. One psychologist, one social worker and the responsible for the social services of the district (psychologist) were called in. I was declared the supervisor of this consultancy group.

We had received a mandate from the mayor’s office. The request to us was to understand the relationship between the socio-political structures and the Sinti and to understand why the housing offer had been refused. To eventually propose alternative projects.

Why the offer had failed was very clear to our consultancy group: there had not been on the part of the politicians any interest on what the needs of the interested part were. The needs were not inquired but just assumed, nor was an analysis of the quest negotiated and made explicit, nor an active participation on the Sinti’ part elicited. The mayor’ office had not worked with the Sinti but projected on their lives.

We decided to go into the camp and speak with the woman who acted as the responsible. After meeting her privately we asked her to call a camp reunion in order to meet with us and help us understand their desires and options according to their stay in the town. Most of the woman came, few man. Since as professionals we were all female, we thought womanhood could become the entering door to the camp. This proved true.

We met with a beautiful old lady with white thin hair in a bond and liquid blue eyes. She seemed a princess. Her son was blind and an excellent cook . Their van was organized with a modern kitchen where he moved around in a very competent manner, as if he could see. He will be the person to cook our last day goodbye meal and there I had the most delicious pinoli pasta in my whole life.

We organized three encounters with the women of the camp who turned out to be very interested in this dialogue. They explained to us – when the relationship became more trustful – that they identity is a vagrant one. Having four wheels underneath their van gave them the illusion of continuing their tradition and of not betraying their roots. Being in a house resulted as claustrophobic. Some of them had utilized the apartments as storage places but not to live in. Inquiring their quests, it came out they would have liked to have a contact with the Italian community they were living next to (the gagi), in order for the children to play together and for them not to feel judged and rejected. Since most of the camp people had converted to evangelic practices[1], they had stopped steeling and beg. The women thought they did not deserve anymore the isolation and the stigmatization, despite they desir to remain a different community and not lose their identity.

At the third encounter at their camp an idea emerged. A time limited project was suggested by some of the woman. The idea was one of a cultural exchange on healing herbs, recipes and remedies between Italian and sinti woman, while the kids were playing together. We chose to implement this possibility and to try and organize this occurrence. We contacted the local social district and got the Italian woman of the district involved. The interest on their part was the possibility of getting to know the sinti culture and the enrichment within the exchange.

Beyond enjoying the conversations that emerged, some explicit aims were established in the first common encounter: recuperate cultural values through the exchange of recopies and remedies, promote woman’s knowledge and emphasize the competences of all. We as professionals had some intentions we had talked about and which emerged – unspoken – during the process: 1. create an appreciative atmosphere, 2. build a sustainable web, 3. try to vanquish the sense of isolation and judgment on the sinti part.

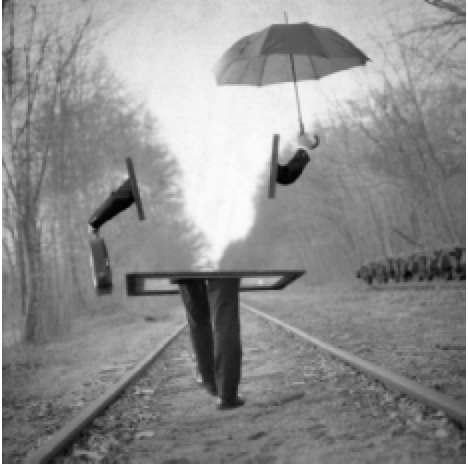

Ten Italian woman and twelve sinti met every Thursday for three months, while some children were drawing and playing together under the care of one of us. Another one of us acted as time keeper, both remembering all the participants of the appointment the day before and preparing the space for the encounter. She was also interested to the content of ancient remedies and actively participated to the process, contributing with her expertise. It was interesting that one resource of the sinti women emerged strongly from the group of Italians: being a wanderer was considered useful in this doubtful world. The roamer was considered a prototypical symbol of these uncertain times, of this particular post-modern culture. Their non belonging to any place shifted from a sign of danger and suspect to one of freedom.

In community work there is a schedule of respect which must be implemented and kept in mind. This we tried to live and obtain. The sense making of what has happened, the life experiences shared resulted more important than what we obtained concretely. No final solution to the isolation problem was searched or reached. A first proposal of dialogue was settled. Our aim has been one of creating a stimulating emotional processes for all the participants, us included. It will take a lot of time to vanquish stigmatization.

The creation of this context of conversation allowed for the construction of a context of trust and connectivity. In order to offer a sense of meaning and to give credit to the initiative we asked the mayor’s office the publication of what would come out from the conversations. We received a promise but the elections and a change in politics made this impossible.

[1] It is interesting how the evangelization took place: the evangelic priest took advantage of their nomadic identity to encounter them every week in a different Italian town, and proposing them this trip as a fundamental aspect of their spiritual process. The evangelic god seems embodied who “puts in the heart fear and love”.